Excerpt of Lewis Hyde’s The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property,

New York, [ Vintage Books ], 1983, CHAPTER ONE, The Motion, Page 3 - 4

Narrator: Elliot Woods

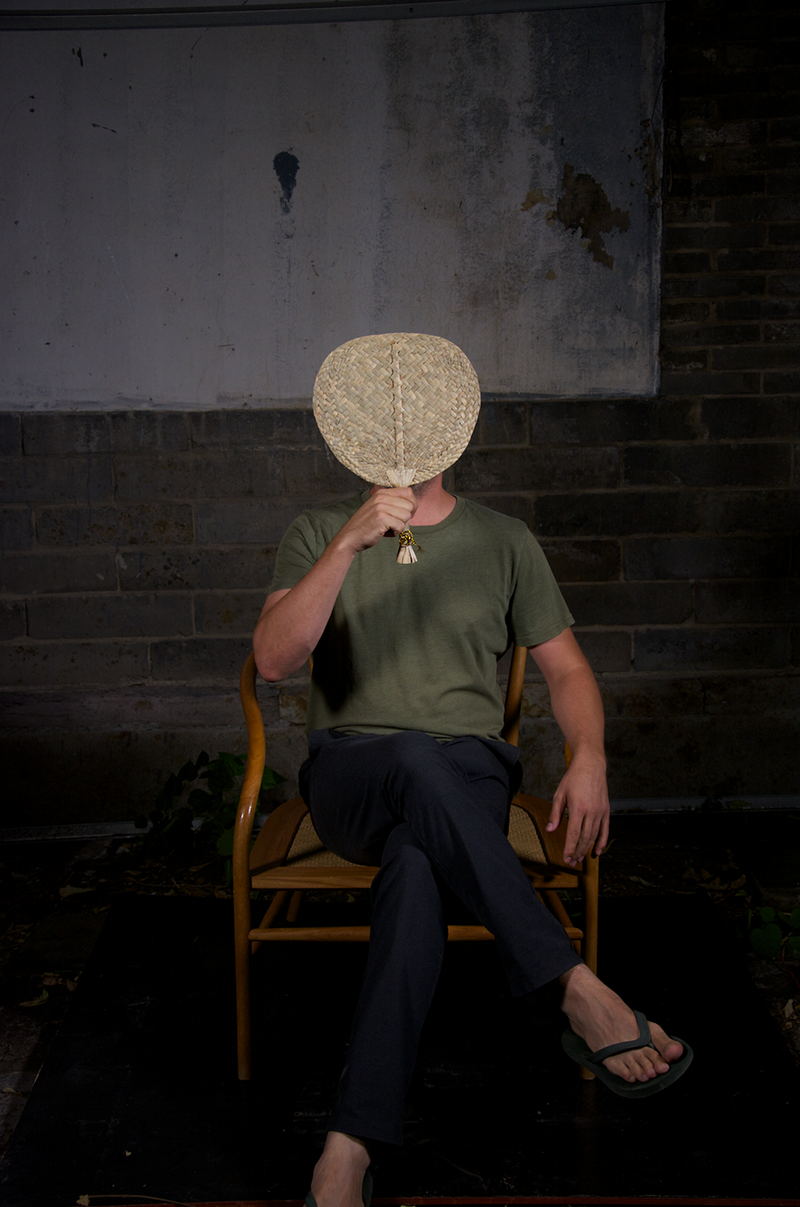

The video consists of documentation material from a gift performance. Before entering a certain room, the audience was presented with an opening speech reciting a fragment from Lewis Hyde's book The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. This passage reveals the twisted notion of a so-called "Indian giver" based on the anecdote of an encounter between an Englishman and Native Americans, where a pipe of peace as a gift given with the intention to further circulate among the people, became misused as a museum artifact. After the opening speech, visitors were invited inside to receive a gift from the artist. More than 80 hand fans from my collection, which were alo used for props in another video, were shown on a long table. Each hand fan was personally given to a visitor who became co-owner of a work of art or gift and a visual part of the exhibition during the opening. As protagonists, they held the gifts in their hands or simply fanned cold air on a hot summer's day.

Gift Giving Performance, 2016, Hand Fans, Shuyu Chen, Max Gerthel, Sascha Pohle

1 When the Puritans first landed in Massachusetts, they discovered a thing so curious about the Indians’ feelings for property that they felt called upon to give it a name. In 1764, when Thomas Hutchinson zwrote his history of the colony, the term was already an old saying: “An Indian gift,” he told his readers, “is a proverbial expression signifying a present for which an equivalent return is expected.” We still use this, of course, and in an even broader sense, calling that friend an Indian giver who is so uncivilized as to ask us to return a gift he has given. Imagine a scene. An Englishman comes into an Indian lodge, and his hosts, wishing to make their guest feel welcome, ask him to share a pipe of tobacco. Carved from a soft red stone, the pipe itself is a peace offering that has traditionally circulated among the local tribes, staying in each lodge for a time but always given away again sooner or later. And so the Indians, as is only polite among their people, give the pipe to their guest when he leaves. The Englishman is tickled pink. What a nice thing to send back to the British Museum! He takes it home and sets it on the mantelpiece. A time passes and the leaders of a neighboring tribe come to visit the colonist’s home. To his surprise he finds his guests have some expectation in regard to his pipe, and his translator finally explains to him that if he wishes to show his goodwill he should offer them a smoke and give them the pipe. In consternation the Englishman invents a phrase to describe these people with such a limited sense of private property. The opposite of “Indian giver” would be something like “white man keeper” (or maybe “capitalist”), that is, a person whose instinct is to remove property from circulation, to put it in a warehouse or museum (or, more to the point for capitalism, to lay it aside to be used for production). The Indian giver (or the original one, at any rate) understood a cardinal property of the gift: whatever we have been given is supposed to be given away again, not kept. Or, if it is kept, something of similar value should move on in its stead, the way a billiard ball may stop when it sends another scurrying across the felt, its momentum transferred. … the gift must always move.

1 Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property, New York, [ Vintage Books ],1983, CHAPTER ONE, The Motion, page 3-4

Opening, Given Time, Institut for Provocation, 2016, CN