This essay is excerpted and adapted from Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (University of Chicago Press, 2014)1

His body, which contains a history, espouses his job, in other words, a history, a tradition, which he has never seen except incarnated in bodies, or more precisely, in the uniforms inhabited by a certain habitus... It can not even be said that he takes himself to be a waiter; he is too completely taken up by the job to which he was socio-logically destined...

—Pierre Bourdieu, 'Bodily Knowledge', in Pascalian Meditations (2000).2

...[T]he waiter in the cafe can not be immediately a cafe waiter in the sense that this inkwell is an inkwell, or the glass is a glass. It is by no means that he cannot form reflective judgements or concepts concerning his condition. He knows well what it "means:" the obligation of getting up at five o'clock, of sweeping the floor of the shop before the restaurant opens, of starting the coffee pot going, etc. But all these concepts, all these judgments refer to the transcendent. It is a matter of abstract possibilities, of rights and duties conferred on a "person possessing rights." And it is precisely this person who I have to be (if I am the waiter in question) and who I am not.

—Jean Paul Sartre, 'Bad Faith', in Being and Nothingness (1943).3

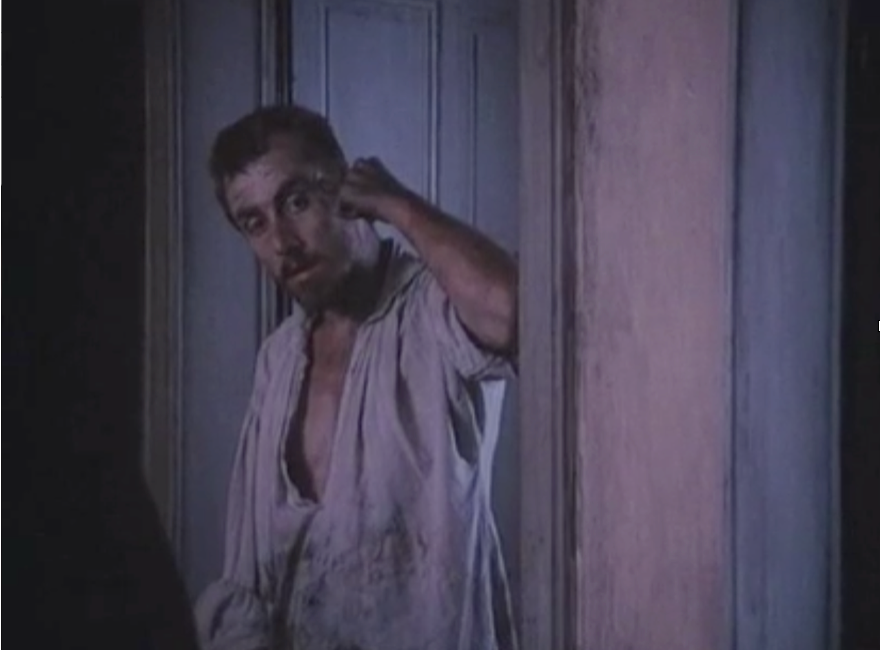

For six months in 2008 and 2009, the German-born, Amsterdam-based video artist Sascha Pohle asked painters working in Dafen village to re-enact scenes from over eighty American and European films. Dafen village, located in the city of Shenzhen, China, had already been made famous as the world's largest production center for oil on canvas paintings, supplying the world's wholesale and consumer market with affordable paintings—most sourced from the Western canon. For his reenactment project, the movies chosen by Pohle depicted artists both famous and fictional, and although they ranged from classics of the twentieth century to lesser forgotten films, each of the scenes Pohle selected dramatized the same invariable traits of the modern artist: his creative genius and pure inspiration, his tortured soul or uncompromising egotism, his scorn for dealers and the art market, his triumph over an implacable teacher, and, of course, his passionate love affairs with his female models. Assigning these clichéd roles to Dafen painters, Pohle asked Hunan-born, van Gogh specialist Zhao Xiaoyong to play Tim Roth as Vincent van Gogh in Vincent and Theo (1990), a female painter nicknamed "Jia Jia" to play Penelope Cruz as the fictional painter "Maria Elena" in Vicky Christina Barcelona (2008), and Liaoning-born, Ding Shaoguang specialist Qin Xiaobin to play Anthony Hopkins as Pablo Picasso in Surviving Picasso (1996). [Figures 1 and 2]

In contrast to the filmic image of the studio artist, Sascha Pohle's practice is that of a contemporary post-studio artist, one who takes on the multidisciplinary and managerial roles of filmmaker, director, assembler and producer. And in keeping with contemporary art's recent globalization, Pohle was working itinerantly—in this case, in China, where he relied on an interpreter, a cameraman and a key local informant to communicate with his subjects and to coordinate the project. Pohle's ad-hoc team found and convinced volunteers to participate, translated the scripts, organized the shoots, and conveyed his directorial instructions to the painters. The reenactments themselves took place in the unmodified settings of Dafen painters' own homes, studios, shops and galleries—unkempt workspaces littered with half-finished canvases and the humble possessions of migrant working class Chinese households. Costumes, makeup and professional lighting were eschewed because, for Pohle, Dafen village was a "readymade film set," automatically the antithesis to the Hollywood image of bohemia.4 [Figures 3 and 4]

For their part, the Dafen painters who had volunteered (without payment) to participate in Pohle's art project had largely done so out of curiosity and collegiality;5 Pohle's was neither the first filmic production to be set in their midst, nor was it the first contemporary art project that explicitly required their appearance. Yet, when the moment of filming began, it was eminently clear how difficult it would be for the painters to portray the filmic roles they had been assigned. After all, they had been asked to "re-enact" scenes taken out of context from movies they had never seen, and to deliver lines they had had little time to learn in Mandarin Chinese, the common dialect which they spoke with thick regional accents and unrefined provincialisms. Their performances were thus filled with half-remembered declarations and meaningless gestures, punctuated by awkward hesitations and silences. [Figures 5 and 6]

Returning to Amsterdam, Pohle edited hundreds of hours of footage into a thirty five minute sequence of short scenes, roughly subtitled back into English—Pohle’s second language—with the assistance of a Hong Kong-born Mandarin-speaking assistant. Buried beneath so many layers of translation and mediation, the original movie scene, which is never shown in Pohle's final video, can hardly be identified, and the Dafen painters overwhelming appear to be untrained actors trying to play a part they have never known. The question the work poses, however, is whether, despite the vast displacement in culture, language, and knowledge staged by Pohle's contrivance, the Dafen painters, in fact, already knew their parts.

Pohle, long interested in celebrity impersonators and historical re-enactors like German "Hobby Indians," began the project to explore the connection between the vocation of "copy- painter" and the popular stereotype of the artist. His initial project proposal, written for the Netherlands Film Fund (which ultimately sponsored the project), asked whether a Chinese van Gogh specialist painter might not be like van Gogh the great artist.6 In other words, Pohle had come to Dafen village wondering, "Did the painters identify with the painters they are copying?"7 When put forth in a context presumed to be radically different from the source of that stereotype (the "West" as expressed in Hollywood film), the question contains within it an implicit hypothesis: that the Chinese copyist might share with his canonical Western referent something beyond the historical contingencies that make them extreme opposites. This presumed connection is grounded in the special skill of painting—and in the Dafen case, in the very special skill of copying another artist's oeuvre. As Pohle put it, he had come to Dafen assuming that, "If you do certain brushstrokes again and again....this repetitive action, the technique, would become a part of the body’s memory, like an automatism of motion comparable with an obsession."8 Pohle's hypothesis, in other words, was that the Dafen painter transcends the historical and social particularities of his situation by the work of his hand, suggesting that, by his skill, the copyist is connected to his distant and revered referent.

Painting, unlike all other skills, but especially unlike the "deskilled" work of industrial manufacture, is privileged as a special kind of work—one that embodies the techniques, traditions and values of art in its finest sense. It is differentiated further from the lower arts or crafts, because it has been conceived as a peculiarly expressive skill, tied to the unique individual who wields it. Painting, in this sense, might called the most artful of "bodily" knowledges—an autographic performance of the hand, whose singular gestures and traces in brushwork grant access to an individual persona. Given the powerful expectation that the artist's persona is somehow embodied in his brushstrokes on canvas, how could a painter who had made his life's work the copying of another painter's entire oeuvre not be somehow like that same great artist?

The initial proposition put forth by Pohle's project thus contained within it an entire apparatus of art appreciation, founded on an ideology of individual creativity at the heart of modernism.9 In the hands of a twenty-first century conceptual artist, these modernist expectations were also concomitant with the image of a world flattened by globalization qua Americanization, on which an earlier figuration of West as precedent and East as follower is expected to play out anew. The intended staging was: Hollywood, the mass-exporter of cultural stereotypes; China, the mass- producer of that reflected mirror image. Underlying this further was the presumption that cultural exportation from the West to China functions by mimetic imitation, and that the Chinese worker strives evermore for the exact, perfect, and mechanical copy. In so doing, it is further presumed, the Chinese copyist also desires to become his Western precedent—whom he is presumed to know through that great equalizer, Hollywood movies. Although these presumptions predictably reproduce the mythic power and superiority of an imagined West, it is the hand—expressive of the modernity of the individual interiorized in the work of art through the skill of painting—that drives its global reach. How, in other words, can a Chinese copyist not desire to be the Westerner he saw in the movies, the false idol whose work he imitates?

Challenging the host of assumptions that make a question like this possible, encounters between Dafen painters and artists like Pohle reveal that it is mediation and intermediaries, rather than mimesis, that characterize the relationship between the lowliest workers of contemporary Chinese painting production and the most elevated works of Western art history. To be able to paint Vincent van Gogh's paintings is not necessarily to believe all that the Western cultural imperialist would like the subaltern other to believe of Vincent van Gogh; To have watched Lust for Life is not to have fallen for all of America's enticements.

Is China really a nation of copycats and the West the fount of all creativity? Is Europe still the center of true art and America, the world's false idol for emulation? Though such propositions today seem blatantly orientalist, the value-laden notions of copying and creativity at its basis are rarely challenged. Instead what is often sought after are counter-examples of Chinese creativity or counter-narratives of Chinese essence—China's twisted resistance to American culture, is, from one respect, envisioned as a validation of Eurocentric values.

Upon stepping into Dafen village, Sascha Pohle soon found that the initial proposition of his project proved untenable. First of all, it had been wrong to assume that the professional specialities of Dafen painters would mirror the Western pantheon of canonical artists: Instead, it turned out that, as a matter of skill, there is no reason why a painter of van Gogh paintings could not also paint a Monet and therefore any Impressionist or Post-Impressionist painting. Likewise, a "figurative painter" in Dafen village could easily encompass the Renaissance, the Baroque, Neo-Classicism and Photorealism within his stylistic and technical range, let alone particular "masterpieces" of Leonardo da Vinci, Gustave Bouguereau, Jacques-Louis David and Chuck Close. Immediately then, the set of assumptions that were meant to follow in Pohle's hypothesis also crumbled: that a copyist need dedicatedly copy one single canonical artist, that he would idolize his referent, that he would identify with him, that he would know his role.

Contrary to the myth circulated by journalists that Dafen painters paint in factory-like assembly lines, Dafen village is a community dealers, artists and painters, each with aspirations and professional competitions strikingly familiar in both elite Western or Chinese artistic contexts. They work much like artists have done in many periods of Western art, and as many professional painters continue to do throughout Europe and America. They paint according to their clients (or patrons) demand, in standardized sizes suitable to domestic spaces where their paintings would be hung, and they were paid for each painting when their buyers were satisfied with them.

The work of Dafen painters thus largely consists in producing a saleable painting, painted on commission, based upon a precedent image, and judged against the work of their competitors and the demands of the market. To produce these paintings, Dafen painters also employ a range of artistic practices that include what art historians would recognize as transfer, transformation, invention, innovation, appropriation, and delegation. Although such techniques are standard fare among modern artists, they are the very techniques presumed to be beyond the skill of copyists.

If Dafen painters had long mastered the tradition of Western oil painting, neither is the Western role of the artist itself very difficult to learn. In order to select film scenes for his re- enactment project, Pohle watched upwards of one hundred American and European films about artists. Despite the vaunted uniqueness and individuality of each artist that each film celebrated, what Pohle found was an unrelentingly repetitive romantic image of the artist, a stereotype that both Pohle and his Dafen collaborators knew all too well. This is a rhetoric so well known that they hardly need spelling out: "Art" comes from gifted and rebellious individuals who struggle alone in their studios. He—and it is almost always a he—rebels against his teachers, who have nothing to

teach him; Women, especially his models, fall passionately in love with him, while his paintings of them are keys to his innermost feelings; He shuns the market and all hints of interest in commercial concern in pursuit of his singular personal vision, which will ultimately bring him worldwide recognition, if only after his death. Even so, his "masterpieces" have an ineffable authenticity to them, they speak of his unique and individual persona, and will someday be recognized by the most sophisticated connoisseurs, and eventually, the whole world. It is a story that surely is pure fiction, and Dafen painters, who have spent years selling thousands of paintings to dealers, know it well.

***

What is an artist? Is it a labor-based identity acquired through skill, a mastery of various methods and means of art-making that enables an individual to transcend technique and repetition, and to achieve, in rare moments, the creativity latent in him/herself? Or are these only cultural constructs, attained through performing the roles acquired through on-the-job training, a distanced and knowing "act," a phony who-you-know and where-you-went-to-school? These two opposing definitions of art each imply a different art historical narrative that brings us to the contemporary moment. By one narrative, practical "deskilling" and social "upskilling" is the story of contemporary qua conceptual art, and the "skills" of the artist are only class-determined constructs that need to be broken through by individual genius. By another narrative, the performances of the celebrity artist are merely the source of frivolous frisson for the petty elite, incomparable to the global heritage of true and original art. The competition between contemporary artists and between definitions of artistic values, are, in other words, also a competition between conceptions of painterly skill and artistic performance, between the performative celebrity-artist and the skill-savvy painter-artist.

Sascha Pohle took these questions to the unique world of Dafen village, a community of Chinese "copyists" who would be expected to offer some kind of overturning of that juxtaposition. His project took the notion of painting skill, traditionally envisioned as a bodily practice, harnessed it to the expectation of Chinese mimesis of Western art history, and tested whether Dafen painters were such skilled copyists that they could also "re-enact" the roles of Western artists.

Yet contrary to his expectation that the copyist would acquire a bodily knowledge that would make him identify with the artist whose work he imitates, Pohle soon observed in his Dafen collaborators something quite the opposite: "I realized that most of Dafen painters remained kind of detached and regarded painting more as a labor job."10 But Pohle also likened their detachment to his own feelings of detachment towards the role of "director" that he had assigned himself in the project.11 In other words, the Dafen painter and the conceptual artist together share an uneasy awareness of the distance between art making as work, and the rather mythic expectations for the artwork to embody the "true" expressions of the "real" artist.

Significantly, though, in the art market in which he operates, Pohle's sense of detachment as a "director" would hardly be seen as a threat to his authorship, for it is considered only a role set, staged, and framed by his social status as an artist. Empowered by art historical narratives of Rembrandt's theatricality, Duchamp's tricksterism and Warhol's impersonation of celebrity, the performances of the conceptual artist are always to be distinguished from his true intentions, stratagems, and skills. Thus the contemporary artist might best be defined as a figure who only dabbles in disciplines like filmmaking and delegates to manually-skilled lower laborers, all the while honing his social skills as an artist.

Yet in the same contexts of reception that would license even the most contrived role-playing in an artist, the Dafen painter's expressed sense of detachment from his work would be understood as a lamentable consequence of his job as a "copyist"—proof of his alienation from the true work of a painter and the realization of his innate creativity. In other words, whereas the contemporary artist's authenticity is constructed to be entirely separate from his manual skills (or lack thereof), the Chinese copyist is presumed to be utterly alienated by it (especially the better he is at it). The copyist's alienation, in other words, is necessary to construct that always unalienated status of the artist.

In painting from precedent images excised from their historical context, remaking and adapting them for the global market (the most unknowable context of all), it turns out that Dafen painters have neither interest nor need to repeat each and every brushstroke of the original, nor to know (let alone re-enact) the historical or fictional persona of the original artist. Though they paint paintings they have painted many times before, "copying" is not their work, and is only their identity vis a vis a highly questionable definition of "originality." It should not be surprising, then, that like artists in many other contexts, Dafen painters and bosses would claim to be more skilled, more original, more artistic, and more creative than most everyone else. And like so many modern artistic contexts, it is the Academy that looms large, whether for those who reject it, for those who have been rejected by it, for those who have already attended, and for those who still desire to go. Dafen teaches us that every artist must articulate him- or herself in relation to art school.

Dafen painters negotiate their (non-Western) ethnicity, (lack of) education and (peripheral access to) the art world, in an effort to claim artistic personas outside their birthrights. Their struggle for a professional identity as contemporary artists is thus a process of attempted transformation from constructed anonymity to precarious authorship, pursued in a context of flux and predetermined failure. This pursuit is itself a multilayered act of language, gesture, culture and work —something between the bodily and social knowledge required of "art," and the bodily and social capital required of "artist." The elitism of confining this work of the self to only "true" artists is thrown into relief when Dafen painters confront, engage with, and are represented by contemporary artists like Sascha Pohle and the many other global conceptual artists who have also visited Dafen village. There is more at stake in examining their encounter than simply the question of whether the Dafen trade painter can occupy the same playing field as his contemporary, the conceptual artist. To entertain the possibility of their correspondence, we need to begin questioning that image of the unalienated artist as that most special of global workers.

Fig. 1

Fig.2

Fig.3

Fig.4

Fig.5

Fig.6

Fig. 1 Anthony Hopkins as Pablo Picasso in Surviving Picasso (1996). Fig. 2 Qin Xiaobin as Pablo Picasso in Surviving Picasso, in Sascha Pohle, Reframing the Artist, still from preparatory version, 2009-2010. Image courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 3 Tim Roth as Vincent van Gogh in Vincent and Theo (1990). Fig. 4 Zhao Xiaoyong as Tim Roth as Vincent van Gogh in Vincent and Theo (1990), in Pohle, Reframing the Artist, still from preparatory version, 2009-2010. Image courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 5 Penelope Cruz as "Maria Elena" in Vicky Christina Barcelona (2008). 6 "Jia Jia" as "Maria Elena" in Vicky Christina Barcelona (2008), in Sascha Pohle, Re-Framing the Artist, still from preparatory version, 2009-2010. Image courtesy of the artist.

1 This essay is excerpted and adapted from Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

2 Pierre Bourdieu, Pascalian Meditations, trans. R. Nice (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2000), 154.

3 Sartre, Jean Paul. Jean-Paul Sartre : Basic Writings. Translated by S. Priest. London: Routledge, 2001, 219.

4 Author's fieldnotes, 30 DEC 2008, 2 JAN 2009.

5 None of the painters who participated in Pohle's project were financially compensated for their re- enactments, though in some cases Pohle purchased or ordered one of their paintings which were later used as a prop in the scene. In the final installation of the work, Pohle had some of these props framed and exhibited alongside the video. Some painters approached by Pohle declined to participate.

6 Sascha Pohle, grant proposal for Nederlands Fonds voor de Film, 2008.

7 Correspondence with author, 19-24 APR 2009.

8 Correspondence with author, 19-24 APR 2009.

9 Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art.

10 Sascha Pohle, correspondence with author, 19-24 April 2009.

11 Sascha Pohle, correspondence with author, 19-24 April 2009.