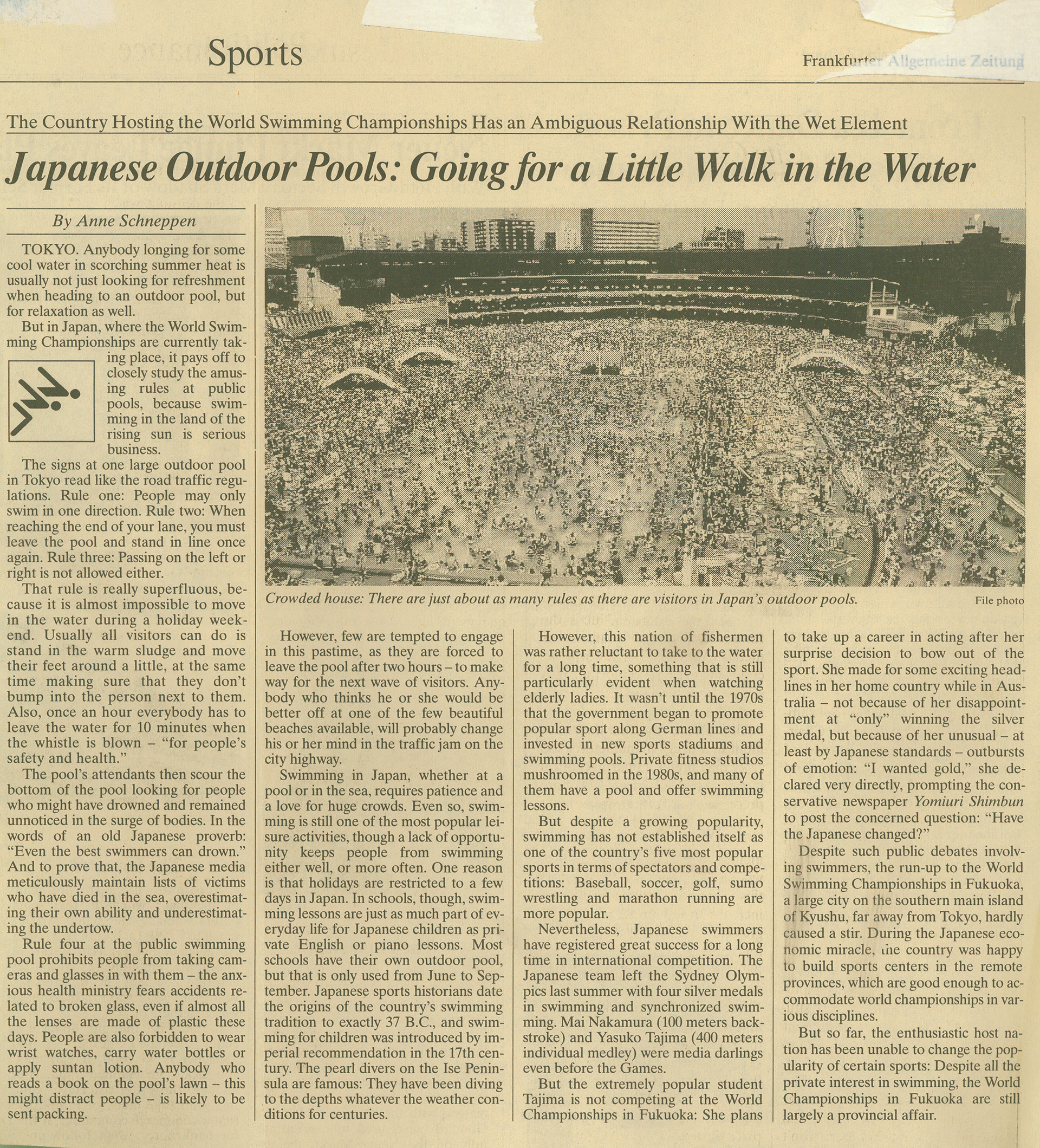

During Tokyo's hot summer days, public pools in amusement parks become severely overcrowded. Rules reminiscent of traffic laws govern behavior, with megaphones constantly issuing safety commands and penalizing infractions. Swimmers must exit hourly for 10-minute safety checks—pools emptied to search for lost items, children, or drowning risks. When drained of bodies, the pools' vivid blue shapes emerge dramatically before the cycle repeats.

Safety Hour reads as allegory for individual and collective fear of death. The "safe" pool—as controlled alternative to the dangerous open sea—reveals its own insecurity. Human crowds, driven by fun and recreation, demand complex safety measures. Humans prove their own greatest danger; masses must be disciplined by fear.

Supported by Kunststiftung NRW

For further readings I can swim home... by Jochen Volz

Jochen Volz, text fragment from ( I can swim home....)

Sascha Pohle’s films, however, are not comparative anthropological studies, precisely for the reason that his choice of the camera angle renders an overview and thus remains at a distance to the individuals. “Safety Hour” is not concerned with examining Japanese bathing culture. Instead, the pool is presented as a general metaphor, as an allegorical image. The onrush of masses can therefore also be interpreted as the image of an overall social phenomenon.

The work Safety Hour be read as an allegory of the individual and collective fear of death. The supposedly safe pool, as an alternative to the nearby open sea with all its dangerous weather outbreaks, animals and currents, is addressed in regard to its insecurity. The human crowd, driven by the yearning for fun and recreation requires intricate safety concepts. Humans turn out to be their own danger and masses have to be transformed under the influence of fear.

One of the most beautiful illustrations of the fountain of youth in the form of a real pool in the modern sense can be found with Lukas Cranach the Elder. The painting from 1546 is in the possession of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Older women come or are brought by relatives from a barren mountain landscape on the left-hand side of the picture. Hopeful and hesitant, they approach the large basin, in the water of which they increasingly rejuvenate. They come out of the water on the right side of the basin as young women. Newly clad und embellished, they indulge in the joys of life and ultimately disappear in the green and fruitful landscape on the right-hand side of the painting. A similar collective yearning luring Cranach’s women to the fountain of youth – men, by the way, did not need to visit the fountain of youth in Cranach’s illustration, because it was assumed at the time that they would rejuvenate merely by socialising with young women – must also motivate the visitors of the swimming pool in a Tokyo leisure park; the common longing for uplift and fun as a magnet for thousands. But the scenes at the pool remind one much more of a plunge into hell by Rubens or of the many and varied illustrations of the damned entering hell, than of Cranach’s dulcet scenario.

With “Safety Hour”, though, Sascha Pohle manages to draw a picture of society that is very peaceful on the outside and in which humans turn out to be their own hazards. While in “The Swimmer” Pohle examines various hotel pools in their peaceful seclusion as the promise of a safe alternative to the nearby open sea with all its dangerous weather outbreaks, animals and currents, in “Safety Hour”, the supposedly safe pool itself, in which waves have to be generated artificially, is addressed quite directly in regard to its insecurity. It is the human crowd, driven by the yearning for fun and recreation, that requires intricate safety concepts, so that people don’t trample each other to death. In Sascha Pohle’s work, the pool time and again serves as a model, and the recordings of the observed phenomena surrounding the pool in Tokyo can therefore be read as an allegory of the individual and collective fear of death.

Safety Hour !, 20 min, color, silent

Safety Hour II, 4,5 min, color, sound

Safety Hour !!!, 9,5 min, color, silent

2004 Espace d'arts contemporaines - Attitudes, Genève, CH, 'Situations construites'

2003 Kulturstiftung Dresden der Dresdner Bank, ‚dynamo.eintracht‘, DE

2003 Kulturstiftung Dresden der Dresdner Bank, ‚dynamo.eintracht‘, DE

Charley 04 (Checkpoint Charley) is born out of the reasearch conducted by the curators of the 4th Berlin biennal for contemporary art (2006) and brought together images of works produced by more than 700 artists.

photo by Karl Moritz